See How Verdansa and George Pakenham have made strides in bringing awareness to idling and enforcing idling laws to help reduce carbon emissions.

New York Magazine - July 10, 2018 George Pakenham is waging a one-man war on air pollution on the Upper West Side

George Pakenham is waging a one-man war on air pollution on the Upper West Side

By Elizabeth Royte

Photographs by Mark Abramson

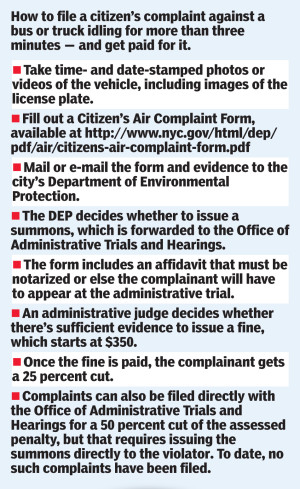

On a sunny March morning, George Pakenham is crisscrossing the streets of the Upper West Side, sweeping the terrain for idlers, drivers who loiter at the curb with their engines running. Although a city ordinance was enacted in 1971 to forbid idling for more than three minutes, it’s rarely enforced, which spurred Pakenham to take matters into his own hands. Under Local Law 717A, which he helped craft and which went into effect in February, you don’t need a badge to bust an environmental scofflaw, only a smartphone and a stomach for bureaucracy. But there’s a sweetener: If you file a Citizens Air Complaint with the Department of Environmental Protection and win the case, you pocket 25 percent of the fine. For Pakenham, a tall Ichabod Crane of a man with a long face and a shock of white hair, that’s added up to $4,300 in less than a year.

“The DEP doesn’t like me,” he says as he briskly crosses Amsterdam Avenue, dodging cars and scanning for idling “tells”: flashing tail lights, tailpipes dripping condensate, or, on hot days, rolled-up windows. “I’ve been a nag. I’m an agitator.” And the cops? “They don’t like me. Idlers are nothing to police — they’re after the big meat.”

Safely over the avenue, we dash across 73rd Street, against the light. Heading east, Pakenham spies a parked van from a tiling company and clicks on his iPhone — the first step in collecting evidence. But no dice, the vehicle isn’t running. We move on. Now, Pakenham, who works in the mortgage department of a bank, spots a decorator’s van. He starts filming the license plate, but within moments the driver pulls away from the curb. Had we been made? I tried to stay out of the driver’s sightline, as Pakenham had warned, but he looks a little annoyed. On we march. The driver of a Pepsi truck, wolfing pizza with the engine going, spots Pakenham’s raised phone, drops the pizza, and pulls back into traffic. We turn up Amsterdam Avenue and come upon an idler from S & J Supply. Pakenham starts the clock, muttering, “He’s in a school zone, no less.” But just as the timer nears the one-minute mark, the limit for school zones, the driver shuts off his engine.

I’m starting to doubt Pakenham’s claim that it typically takes no more than ten minutes to capture a lawbreaker on film. Then we approach DB Trucking, on Columbus. Casually, as if he’s a tourist shooting the local scenery, Pakenham photographs the company’s name and address, displayed on its door, then goes in for the license-plate kill. He photographs the nearest street address and starts to film the truck, with a time and date stamp. “You can hear the engine is on,” he whispers to his camera, then turns off the video while the stopwatch runs. (The DEP requires video evidence of only the beginning and end of the idling period.) Near the four-minute mark, Pakenham turns the camera back on. “Got ’em,” he says.

Minutes later, he spots an idling van from the DEP itself. “That’s futile,” he says. “The city is never going to squeal on one of its own agencies.” Other lessons from the master: Forget about armoured trucks (best not to piss off people with guns); UPS (no address on the truck); ambulances (they’re exempt from the law); and passenger cars (the DEP accepts complaints only for commercial vehicles). The biggest violators, in Pakenham’s experience, are plumbers, electricians, and carpenters.

And then there’s his bête noire: ADT Security Services. On Columbus, we come upon an ADT driver typing away on his laptop. Pakenham clicks on his camera and asks me to cup the van’s tailpipe, to confirm that the vehicle is running. Affirmative. “The company got a $350 fine about a month ago, thanks to me,” Pakenham gloats. “I got $87.50 of that.”

Pakenham has had exhaust fumes on the brain at least since Operation Red Dawn, in 2003. Americans were dying in Iraq for what he considered an oil grab; passenger cars in New York City were burning through 150,000 barrels of oil a day, and his brother — a nonsmoker — was diagnosed with lung cancer. Those tailpipe emissions, he learned, were not only warming the air but flooding it with compounds linked with asthma, cancer, and other diseases. The city, he’ll tell anyone who will listen, attributes more than 3,000 deaths a year to air pollution.

George Pakenham at work. Photo: Mark Abramson for New York Magazine

In the early days of his crusade, Pakenham would start his encounters with the international gesture for “roll down your window.” Then he’d say to drivers, “I’m sorry to bother you, but are you aware that idling for more than three minutes is illegal?” Eighty percent of the time, they’d turn off their engines, he estimates. Others simply drove away. Some asked if he didn’t have better things to do with his time, and once a driver suggested: “Why don’t you put your mouth around my tailpipe?”

Eventually Pakenham printed up small cards that he gave to drivers detailing the anti-idling law and its schedule of fines for first and repeat offenders, which now range from $350 to $2,000. The cards shortened the length of his encounters, which allowed him to initiate more of them: Between 2006 and 2011, he says he rapped on more than 2,900 windows “in a quest for undisputed data.”

In 2012, Pakenham made a documentary about himself called Idle Threat, which screened at film festivals and is available through iTunes. But vehicles were still idling! In 2015, he decided to file a Citizens Air Complaint through a rarely used form on the DEP website. The form contained ambiguous parameters and said complainants “could” reap up to 25 percent of a resulting fine but didn’t guarantee it. “I filed four claims as a test of the system,” Pakenham says. All were rejected by the DEP. “They say I had insufficient evidence. I wept over this,” Pakenham says in all earnestness. “My efforts were for naught.”

But Pakenham, whose activist streak was forged in the crucible of the Vietnam War era —“That was a meaty time for voicing your opinion when you saw injustice” — would not be deterred. He filed paperwork to challenge the DEP decision, and on December 5, 2016, he and the accused idlers were shown into a judge’s chamber and sworn in. This time, his photographic and video proof was deemed sufficient — he won all four cases and pocketed $700.

And so began the latest chapter in Pakenham’s crusade: No more driver’s education. He goes straight for the money. Thanks to the new city ordinance that turned the DEP’s administrative rule into law and strengthened its wording, he’s assured that winning on the first go-round will net him a quarter of the fine. And if his claim is rejected but he prevails on appeal, he gets half. His goal? “Ten scofflaws a week.”

In January, New York University economics professor Karl Storchmann invited Pakenham to his class to help make the case that “Economics decides what is efficient and what isn’t.” The 311 system routinely receives 800 idling complaints a month (up from 50 in 2004), Storchmann told his Urban Econ students, but the police, and the DEP, write summons only if they witness a violation. In 2016, cops issued 2,400 idling tickets, according to Storchmann. (For comparison’s sake, they wrote 105,394 for public drinking, 22,917 for public urination, and 75 for having sex in a park.)

“So much effort goes into the 311 system,” Storchmann lamented. “The city can map heat, rats, potholes and noise, but the idling data is totally unused.” Where the law has failed, Storchmann said, the bounty system — as demonstrated by one George Pakenham — may have the power to modify human behaviour. Indeed, after the class viewed Idle Threat, the first question put to Pakenham was: “Can anyone file and make money from these complaints?

The short answer is yes, though at the time only he and an attorney with the Environmental Defense Fund had successfully used the system. By the end of June, however, Pakenham had trained four “street agents,” as he calls them: a creative director from Brooklyn, a retired photographer, an election worker, and a real estate agent. Together, they’d filed 44 complaints. (He’s up to 80 himself, with another 50 in the pipeline.)

The students were obviously psyched about the chance to earn beer money, but on his way out Pakenham reminded the would-be vigilantes that the overriding goal is to burn less fuel. “It’s remarkable that an idiot like me could be rewarded for this,” he says, adding that he’ll teach anyone who’s interested to join his crusade. “It’s not that difficult. I just want to resolve this stupid problem.”

New York Post - July 6, 2018

The Big Apple’s streets really are paved with gold — for anyone willing to rat out idling trucks and buses.

The city is paying cash bounties to tipsters who turn in commercial drivers for leaving their engines on while parked by a curb for more than three minutes — or a mere minute in a school zone.

The rewards amount to 25 percent of the fines imposed, which range from $350 to a maximum of $2,000 for a repeat offence.

And time-stamped photos or videos are all the evidence that’s needed to file a complaint with the city Department of Environmental Protection.

Since a new law went into effect in February, the agency has received 210 citizen complaints that led to 61 summonses, 20 of which were sent to the Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings, officials said.

The office’s judges have so far upheld four of the tickets, imposing fines of $350 each, with the tipster rewarded $87.50 each time.

The office couldn’t detail how the other 16 summonses were resolved and said hearings had yet to be set for the other 41.

The DEP has an official complaint form and detailed instructions available on its website but hasn’t publicized the potentially lucrative pollution-control program.

Officials said the agency might advertise in the future if it doesn’t start receiving more citizen complaints.

Officials said the agency might advertise in the future if it doesn’t start receiving more citizen complaints.

The bounty program was enacted following more than a decade of anti-idling activism by George Pakenham, an Upper West Side banker who was the subject of a 2012 documentary film titled “Idle Threat: Man on Emission.”

Last year, he told a meeting of the Hell’s Kitchen South Coalition that he had netted $3,000 in judgments against bus companies by commencing civil proceedings under terms of the city’s Administrative Code when the DEP declined to prosecute cases he referred.

In an email last year, he also boasted that “clean air can be monetized . . . to the benefit of all,” according to a source who received the message.

Records obtained by The Post show Pakenham scored one of the recent rewards, for reporting an Air-Wave Air Conditioning Co. truck he caught idling at West 74th Street and Amsterdam Avenue in Manhattan on April 7.

The three other bounties all went to Dominick Eckenstein, a former Brooklyn resident who now lives on a farm in upstate Copake.

His payouts came for reporting a Mueller Distributors beverage truck outside a restaurant in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, a Trailways of New York bus on Eighth Avenue near Times Square, and an ACV Enviro waste-removal truck near City Hall.

All three of those incidents took place in January, but Eckenstein got paid because the hearings were held after the law went into effect, officials said.

Eckenstein said he had filed more than 20 complaints after learning about the new law “through a friend,” but he wouldn’t say it was Pakenham, who declined to comment.

Just four people filed the complaints that led to all 61 summonses, with the other two identified by the DEP as David Dong, whose LinkedIn profile identifies him as a banker, and Tevin Grant, a DEP lawyer.

Neither returned messages seeking comment, and officials said it wasn’t clear whether Grant would be eligible to collect on his complaints.

New York City has restricted curbside idling of all motor vehicles since 1971, with exceptions for emergency vehicles and vehicles whose engines are needed to run refrigeration units or lifts.

Exceptions are also made for buses with passengers that need to use their heating or cooling system while temporarily parked.

Councilwoman Helen Rosenthal (D-Upper West Side) was the prime sponsor of the reward provisions, which she first introduced almost three years ago.

“Vehicle idling is one of New York City’s most intractable environmental issues... but the law is extremely difficult to enforce,” said a spokeswoman for her office.

NYU - March 4, 2017

Depending upon age and level of health, the average person takes between 17,000 and 23,000 breaths a day. Essential to life, the air we breathe should not make us sick.

Under most circumstances, air pollution is invisible, and yet the deaths of 6.5 million people per year are linked to breathing bad air. That’s more deaths due to breathing bad air than from AIDS, auto accidents, cholera, malaria, and war combined.

There are 1.2 billion cars on the road today, 2 billion projected for 2035, 1446 operating coal-fired power plants, and an additional 2291 coal-fired plants either under construction or in planning stages. In NYC alone there are over a million buildings and each is burning some type of fossil fuel to warm people who live or work within them. All those chimneys and pipes are pouring combustion by-products into the air we breathe which affects the health and well-being of all.

The Air We Breathe was a panel comprised of special guests who who spoke from their expertise to identify the danger in every breath and to show us what we can do tomorrow and today: Garth Lenz fine art photographer, Fred Ritchin, Dean of the International Center of Photography, Dr. George Thurston Professor of Environmental Medicine, Dr. Maureen George PhD, RN, AE-C, FAAN, Deborah Goldberg, Managing attorney, Earthjustice, Eric Weltman, senior organizer, Food and Water Watch, George Pakenham, filmmaker Idle Threat, Peter Terezakis, Associate Arts Professor, NYU Tisch and panel organizer.

The panel presentation was followed by a Q & A where experts answered questions about the air we breathe.

The Air We Breathe, was sponsored by the Tisch School of the Arts