New York Times - Feb. 27, 2020

The singer Billy Idol (yes, that pun is intentional) is supporting the campaign, which includes rewarding people who report infractions.

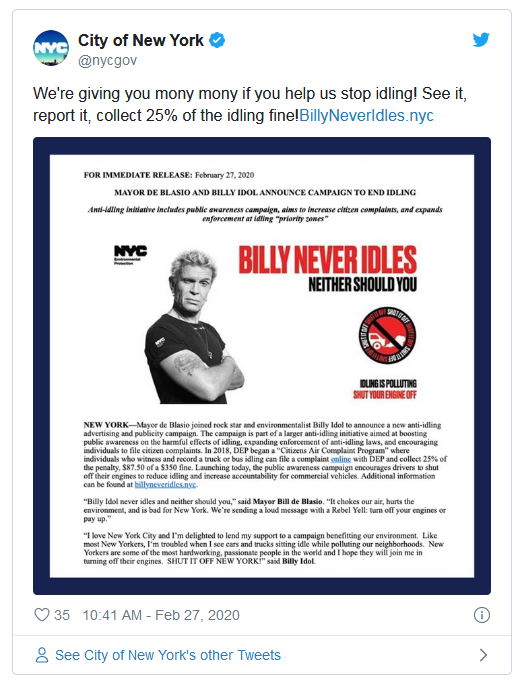

Billy Idol, right, donated his time and likeness for the campaign against idling vehicles in New York City.

By Jeffery C. Mays

With music blaring from concert-sized speakers, the two Bills walked toward the lectern outside City Hall. One was indisputably an Idol; the other was Mayor Bill de Blasio.

Two large posters of the singer Billy Idol, the years turning his trademark sneer into something of a smirk, hung in the background. Then the music — “White Wedding,” one of Mr. Idol’s biggest hits from the 1980s — faded out, allowing the puns to begin.

“It’s a nice day to start again,” Mr. de Blasio said, stealing a lyric from the song.

What brought the two Bills together was a new campaign that aims to prevent trucks and buses from idling by getting New Yorkers to file complaints with environmental authorities.

The program requires participants to capture several minutes of cellphone footage of the idling commercial vehicle in question and send it to the Department of Environmental Protection. If the information leads to a fine, the complainant is eligible to receive 25 percent of it.

The city has already paid out at least $175,000 to informants, covering 2,000 violations. Another 3,000 potential violations are still working their way through the system.

“You can shut off your engines and save my health, help my lungs. I need my lungs to breath and sing,” said Mr. Idol, who lives in Los Angeles and said he mostly rides a motorcycle.

“I’m thinking about coming back, most definitely. Especially with all this clean air,” Mr. Idol said.

The campaign — “Billy Never Idles. Neither Should You” — naturally led to a chant-along led by Mr. Idol, following his claim that “Billy never idles. No way!”

Mr. Idol did not address any possible ethical ramifications of informing on a fellow New Yorker, but city laws clearly encourage it: Helen Rosenthal, a city councilwoman, sponsored the legislation that created a mechanism for people to report the idling and profit from it. It look effect last year.

But before officially answering questions on Thursday, Ms. Rosenthal had a more pressing matter to attend to.

“I’m going to use this opportunity to take a selfie,” she said, proceeding to snap a shot with Mr. Idol.

Ms. Rosenthal said that the soot and particles from idling lead to higher risks of asthma, heart disease and cancer, particularly in low-income communities that serve as truck thoroughfares.

Trucks and buses are not allowed to idle for more than one minute near a school or three minutes anywhere else in the city. Those wishing to report an infraction and collect a share of any fine must capture three minutes of video of a truck or bus idling near a school and four minutes elsewhere.

If the city has an unofficial expert in catching idling scofflaws, it would undoubtedly be George Pakenham, 70, of the Upper West Side.

Mr. Pakenham made a 64-minute documentary in 2012 called “Idle Threat,” where he illustrated the health risks associated with idling vehicles and politely confronted motorists he caught in the act.

Mr. Pakenham said he was motivated to help end idling because his brother died of lung cancer at the age of 58. “Billy Idol has little to do with it,” he said. “I like clean air.”

But he said he does appreciate Mr. Idol’s willingness to throw his celebrity behind an effort to make New York City’s air cleaner. Mr. Pakenham has also profited from his passion: He said he has collected almost $17,000 from the city by reporting idlers.

Fines range from $350 for first-time offenders to $2,000 for repeat violators. A successful first-time fine could yield $87.50 for the complainant.

The idea to bring in Mr. Idol came from the Environmental Protection department’s marketing team, who cold-called his representatives to pitch it.

Mr. Idol, who spent time in Long Island as a child and then lived in New York during the 1980s, said he was looking for a way to give back to the city. He became a United States citizen in 2018.

Mr. Idol’s advertisement will appear on billboards, gas stations, television, radio and social media. He is donating his time and likeness to the city for the advertising campaign, which will cost $1 million in taxpayer money, according to the Environmental Protection commissioner, Vincent Sapienza.

Mr. Sapienza provided that sum in response to a question from Katie Honan, a reporter for The Wall Street Journal, who framed her query through a liberal adaptation of another song made popular by Mr. Idol.

“Can you tell us how much ‘Mony, Mony’ the city is spending?” she asked.